The First Essay In This Series: Missivies on The History of US Trade

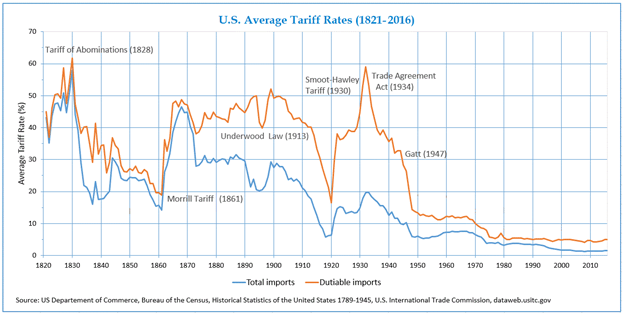

Last week, we outlined a framework from Douglas Irwin’s “Clashing Over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy. That framework suggested American trade policy has consistently pursued three primary objectives throughout its history: Revenue, Restriction, and Reciprocity. This week, we examine the era from before the Revolution to the Civil War and utilize that framework to unpack the trade policy debates of the past to see what lessons we can learn about today's political wrangling.

America's trade policy debates have followed a remarkably consistent pattern from colonial times through the present day, driven less by abstract economic theory than by shifting coalitions of regional interests, security concerns, and the eternal struggle between protection and openness. These foundational tensions continue to shape contemporary discussions about rare earth minerals, steel industry consolidation, and the broader question of economic nationalism in an interconnected world.

The Colonial Foundation: Commerce as Power

The American experience with trade regulation began not with independence, but with rebellion against Britain's Navigation Acts, which required tobacco to be shipped through London ports and inflated the cost of Asian imports. These mercantilist constraints taught colonists that trade rules were instruments of political control rather than neutral economic arrangements. When Britain tightened enforcement after 1763 to pay for the Seven Years' War, the colonies had their first lesson in commercial coercion, a lesson they responded to by boycotting British goods. The political impact of these boycotts far exceeded their economic effect, creating the dangerous illusion that America possessed significant commercial leverage over its major trading partners.

This early experience with commercial coercion would prove prophetic. Jefferson's embargo of 1807-1809 demonstrated the limits of using trade as a weapon, shrinking American GDP by approximately five percent while failing to force Britain or France to respect neutral shipping rights. The embargo's failure foreshadowed the mixed record of modern economic sanctions, where domestic adjustment costs often exceed the foreign policy benefits achieved. Contemporary chip export controls on China and debates over critical mineral export restrictions echo Jefferson's hope that our markets represented economic leverage. Still, effectiveness hinges on the same factors that undermined the embargo: allied coordination, domestic political sustainability, and the target nation's ability to find alternative suppliers.

The Infant Industry Precedent and Modern Rare Earth Strategy

The War of 1812 marked America's first significant experiment with infant industry protection, as disrupted imports spurred domestic cotton textile production. When peace returned, New England mill owners successfully argued for continued tariff protection, establishing a template for strategic industrial policy that persists to this day. The 1816 Tariff raised duties to the mid-thirty percent range, justified by defense needs and the temporary nature of the assistance. Crucially, this protection succeeded: by 1850, American mills produced ninety percent of domestic cloth despite subsequently reduced tariffs, proving that well-designed infant industry policies could achieve genuine competitiveness.

The parallels to contemporary rare earth policy are striking. The Pentagon's investment in MP Materials announced just this week, which made the Department of Defense the company's largest shareholder, mirrors the early Republic's approach to nurturing strategic industries. Like the textile mills of 1816, rare earth processing faces the challenge of competing against an established foreign supplier—in this case, China rather than Britain—while building domestic capacity essential for national security.

The historical precedent suggests several critical factors for success. First, protection must be temporary and conditional on achieving genuine competitiveness. The 1816 tariff was effective because it gradually reduced the percentage over nine years through Clay's Compromise of 1833, forcing mills to achieve efficiency rather than perpetual dependence. Second, government support must crowd in rather than crowd out private capital. The DOD’s investment in MP Materials was accompanied by not only $1 billion in separate bank-led financing but also a $500 million deal with Apple, and an equity raise of $650 million this week. It is not yet clear whether the scales balance (government vs. private), but at least at first glance, this industrial policy action appears to have crowded in. Third, the protected industry must demonstrate learning effects and scale economies that justify the temporary disadvantage to downstream users who pay higher input costs.

Regional Coalitions and Economic Nationalism

Henry Clay's "American System" of the 1820s provided the most explicit early articulation of economic nationalism, linking protective tariffs, internal improvements, and a national bank into a coherent vision of domestic development. Clay's coalition united Mid-Atlantic manufacturers with Western raw material producers, creating a powerful political alliance that persisted for decades. However, this coalition came at the cost of Southern opposition, culminating in the Nullification Crisis of 1832-33, when South Carolina declared federal tariffs unconstitutional.

The nullification crisis illustrates both the potential and the perils of economic nationalism. On the one hand, Clay's system successfully promoted industrial development and infrastructure investment, thereby strengthening the young nation's capacity. On the other hand, it created regional tensions that nearly fractured the Union, as South Carolina planters viewed tariffs as a form of sectional tribute that transferred wealth from agricultural exporters to Northern manufacturers. The crisis was resolved only through Clay's Compromise of 1833, which gradually reduced tariffs to revenue-only levels, demonstrating that even successful economic nationalism requires political sustainability across regional interests.

Contemporary debates over steel industry consolidation reveal similar dynamics. The bipartisan opposition to Nippon Steel's fourteen-billion-dollar acquisition of U.S. Steel reflects the enduring appeal of economic nationalism when applied to "strategic" industries; however, the historical record cautions against conflating national ownership with national interest. The antebellum iron industry's protection from British competition ultimately slowed technological adoption, as American producers remained wedded to charcoal-based production while Britain revolutionized steelmaking with coke-fired blast furnaces. Douglas Irwin estimates that while import price fluctuations on prig iron had a much greater impact on US production than changes in import duties, the tariffs permitted domestic output to be about thirty to forty percent larger than it would have been without protection. Similarly, blocking efficient foreign ownership of American companies could hinder the adoption of lower-cost production methods or the implementation of best practices learned from different operating environments.

The Limits of Commercial Coercion

The repeated failure of commercial coercion represents one of the most consistent themes in American trade history. Colonial boycotts succeeded politically by mobilizing domestic opposition to British policy, but their economic impact remained modest because Britain's American market represented only fifteen percent of total exports. Jefferson's embargo proved even more damaging to American interests than British ones, forcing repeal after economic devastation and political revolt. The pattern continued through the twentieth century, as successive attempts to use trade as a foreign policy instrument achieved mixed results at best.

This historical experience provides crucial context for evaluating contemporary trade conflicts. The United States' position as the world's largest economy offers significant leverage, but that leverage diminishes when target nations can find alternative suppliers or when domestic constituencies bear substantial costs from trade restrictions. The semiconductor export controls imposed on China represent a sophisticated attempt to avoid the embargo's mistakes by focusing on specific technologies rather than broad economic sectors. Still, their effectiveness will ultimately depend on the participation of allied forces and the target's ability to develop substitute capabilities, the tariffs may even be the proximate cause of substitute development.

Revenue Needs Versus Distributional Politics

The early Republic's experience with tariff policy was fundamentally shaped by the federal government's desperate need for revenue, as import duties provided the overwhelming share of government funding. This fiscal constraint limited the scope for purely redistributive policies, since tariffs that reduced imports also reduced government income. The Walker Tariff of 1846 exemplified this revenue-first approach, establishing uniform ad valorem rates designed to maximize collections rather than protect particular industries.

Modern trade policy operates in a fundamentally different fiscal environment, as the federal government no longer relies on tariff revenue and can finance its operations through income taxes and borrowing. This shift has profound implications for the political economy of trade protection, since every tariff now represents pure redistribution rather than necessary revenue collection. The result is more intense political scrutiny of trade policies, as affected constituencies can no longer appeal to shared fiscal needs but must justify protection on grounds of competitiveness or security.

This transformation helps explain the contemporary focus on "strategic" industries and supply chain resilience rather than broad-based protection. The CHIPS Act, battery subsidies, and rare earth investments all invoke national security justifications that transcend narrow economic interests. However, the historical record suggests that security justifications can easily become pretexts for garden-variety protection, as domestic industries develop vested interests in continued government support.

Lessozs for Contemporary Industrial Policy

The historical arc of American trade policy offers several enduring lessons for contemporary debates about tariffs, industrial strategy, and economic nationalism.

First, successful industrial policies must be temporary and performance-based, with clear metrics for success and sunset provisions that prevent the creation of permanent dependence. The early US textile industry's transition from a protected to unprotected industry demonstrates that infant industry policies can be effective when properly designed, but only if they include credible exit strategies.

Second, industrial policy succeeds best when it works with, rather than against, market forces, providing temporary support that allows competitive industries to emerge, rather than permanent subsidies that preserve inefficient production. The Pentagon's equity investment in MP Materials represents a more sophisticated approach than simple tariff protection, as it aligns government and private incentives while maintaining market discipline through public listing and private co-investment.

Third, trade policy must account for coalition dynamics and regional impacts, as policies that benefit one region at another's expense can create political instability that undermines long-term effectiveness. The nullification crisis illustrates how successful economic nationalism can generate its own opposition, necessitating careful consideration of distributional consequences and political sustainability.

Fourth, commercial coercion remains a blunt instrument with limited effectiveness, particularly when target nations have alternative suppliers or when domestic constituencies bear substantial adjustment costs. The semiconductor export controls on China represent a more targeted approach than Jefferson's embargo; however, their ultimate success is still an open question.

Finally, the distinction between revenue-generating and redistributive trade policies has profound implications for political sustainability of a trade or economic policy. Modern trade interventions lack the fiscal justification that made tariffs acceptable in the early Republic, requiring stronger arguments based on security, competitiveness, or technological leadership. While, in theory, this higher bar for justification should improve policy design by forcing more careful analysis of costs and benefits, it is far from clear that the theory is playing out in reality; if anything, it appears the opposite. The lack of a unifying justification seems to be creating an opening for less substantive, more performative arguments to prevail.

For investors navigating today's trade policy landscape, the historical perspective suggests focusing on sectors where government intervention serves genuine strategic purposes rather than narrow political interests. The rare earth industry's combination of security importance, technological complexity, and foreign supply concentration makes it a more credible candidate for sustained government support than traditional manufacturing sectors (for example, automotive manufacturing or steel) that are simply seeking protection from foreign competition (although it should be noted that automakers are not found of the current tariff regime, they are being “protected” against their will). Similarly, industries that can demonstrate learning effects and scaling are more likely to justify temporary support than those seeking permanent shelter from market forces.

The long arc of American trade policy reveals that successful industrial strategies require careful attention to both economic fundamentals and political dynamics, combining market discipline with strategic vision while maintaining the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances. As policymakers grapple with contemporary challenges, including supply chain resilience and technological competition, the historical record provides both inspiration and caution about the possibilities and limitations of using trade policy to serve broader national objectives.